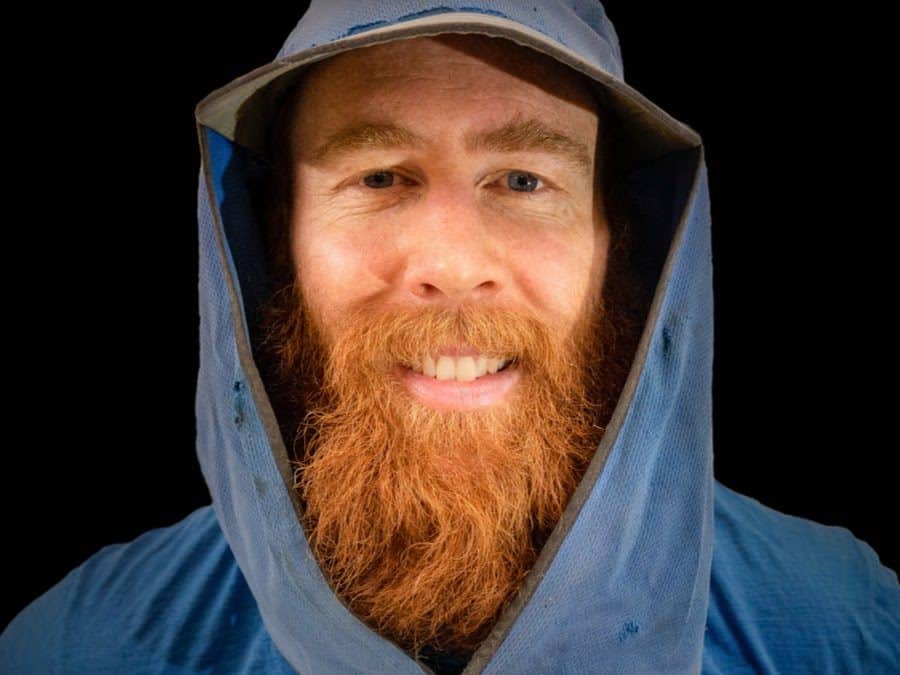

Beau Miles

Beau Miles

It is summer-time in Australia.

While scrolling though YouTube in recent days, I came across a most unusual character from “Down Under.” Story-teller extraordinaire, adventurer, and filmmaker, Beau Miles sports a bright orange beard, a mop of wavy dark hair, an infectious smile, and speaks in Australian-accented English.

“He has traveled to all corners of the globe on a shoestring budget, always in search of backwaters and backstories.”

Beau achieved a PhD in Outdoor Education at Melbourne’s University of Monash, where he has lectured for a dozen years, but he lives in Jindivick, Victoria, 90 kilometers east of Melbourne, on a farm, surrounded by the greenest of pastures, and thick groves of old gum and eucalyptus trees.

He made a video once of how he walked 90 kilometers to the university, where he gave a lecture.

Four years ago, Beau ran the 655-kilometer Australian Alps Walking Track, that follows the alpine areas of Victoria, New South Wales, and the capital of Canberra, first person to achieve that. He also kayaked 2,000 kilometers from Mozambique, to Cape Town, South Africa, along Africa’s east coast.

Three years ago, Beau kayaked across the Bass Strait between the city of Melbourne and the island of Tasmania, and recorded his adventure in a video, “Bass by Kayak.”

In recent years, Beau married Helen, and in October of 2019, she gave birth to their daughter May. With a family, Beau now stays closer to home, and Helen and May both appear in his videos.

Beau collects wood and old planks of lumber that others have tossed aside, and that he stores underneath his house. He admits, “I have a love affair with wood.” Two years ago, he made a video showing how he made a kayak paddle from odd pieces of junk lumber he picked up alongside the road.

Two years ago, Beau decided to run a marathon, 26+ miles, but do it over 24 hours. He measured the road that loops around his farm and discovered that it completes a full mile. At noon on the first day, he ran three laps, and then at the beginning of every hour thereafter, he completed a single lap.

Between laps, Beau shifted into high gear, was in constant motion. He says, “The rest of the time I do as much as possible; making things, odd jobs, fixing stuff. It’s about running, doing, and thinking.”

He planted a series of small trees. He cooked vegetables and baked a loaf of bread in pots over hot coals. He and Helen then ate the vegetables and bread. He pulled out some of his junk lumber, grabbed his power saw, power sander, power drill, and made an outdoor table.

On a grease board, he listed all the things he wanted to accomplish that day, and once completed, he crossed each off. One of his items was, “eat an orange.” Once he ate it, he crossed it off.

But at the beginning of each hour, he stopped, headed to the road, and ran another lap. Helen ran a lap or two with him in the dark that night, their way lit with a light strapped to Beau’s forehead.

Beau completed the marathon just before noon the following day.

One guy who watched this 17-minute video, said, “This guy is having a manic episode on YouTube, and we are just cheering on his madness, lol.” Another said, “This is the most productive mid-life crisis ever!” A house wife said, “This is every wife’s dream, a man actually doing all the tasks in one day.”

The video’s title is “The potentials of a single day—A mile an hour,” and towards its end, he says, “I may have just had the ultimate day of running and making and fixing and being.”

Yes, without preaching, Beau Miles demonstrates how a man or a woman, a boy or a girl, could accomplish in one day far more than what they would dare to believe. How?

Beau’s techniques are not extraordinary. They include a plan to run, a simple to-do list, and a steady supply of needed goods within easy reach: power tools, scraps of lumber, a shovel, small trees, flour, yeast, vegetables, iron pots, hot coals, running shoes, and an old-fashioned alarm clock.

He follows the advice I heard decades ago, “plan for tomorrow by writing down tonight all you want to accomplish the next day.”

Beau’s single day reminds me of a poem written by the Scottish poet, Thomas Carlyle, “To-Day.” “So here hath been dawning another blue day; Think, wilt thou let it slip useless away? Out of Eternity this new day is born; into Eternity, at night will return.”

You and I are blessed. We head into a new year, 2021, and we now have a few days less than 365 to live. Do we dare give each day over to “running and making and fixing and being?”

Oh, yes, it is summer in Australia, a pleasant thought these cold days in January.