Plagues

Plagues

Rarely do men and women seem free, even for a moment, from the evils that have plagued human beings for millennium: war, poverty, famine, slavery, racism, diseases, pestilence, and natural disasters.

The U.S. armed forces first attacked the Taliban in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, and now, the twin wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are winding down after two decades, wars that have cut short many human lives and caused painful, debilitating injuries. On the horizon is a menacing conflict with China.

Poverty and famine often arrive together. During a famine, the poorest starve. In the past hundred years, the worst famines have struck hard the poorest peoples of India, China, and Russia.

Racism begets slavery. When one race, class, or culture views another as weak and less-than-human, the superior will try to enslave the weaker. “Enslave them, work them, refuse to pay them.”

On occasion, some have resorted to mass murder to eradicate another race, class, or culture. The Nazi’s sought to destroy the Jewish population across Europe in the 20th century, and in a prior century, greedy European settlers looked through Native Americans, hoping to steal their land.

Certain diseases—cancer, heart attacks, diabetes, and arthritis—unleash an ocean of misery, pain-filled days, and shortened lives. No one signs up for these very human diseases.

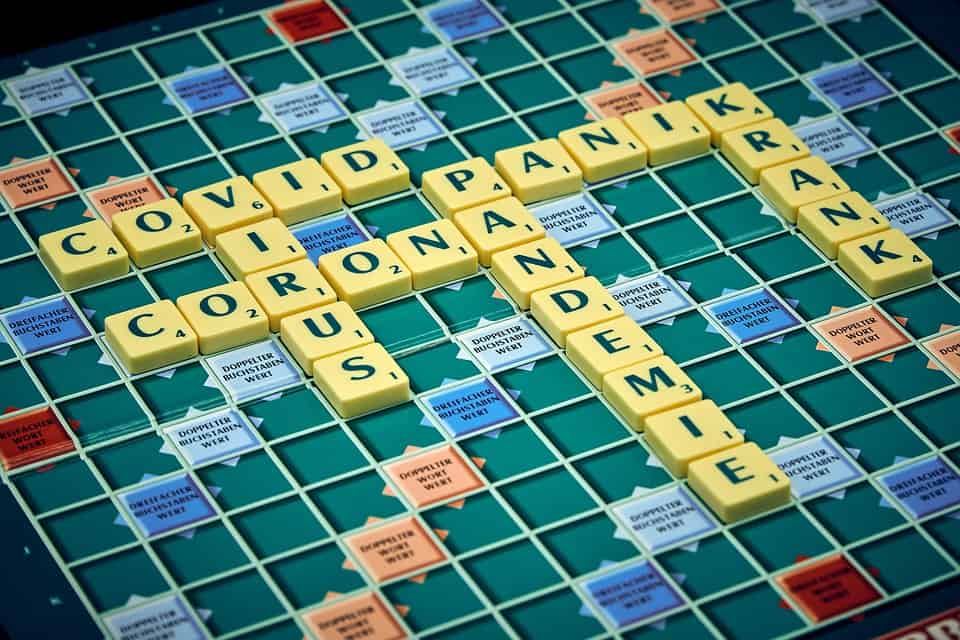

Modern human beings almost forgot about pestilence. Then, eighteen months ago, from out of China, came a coronavirus carried by bats that has cut a deadly swath through the world’s human population. Now, men, women, boys, and girls, must prepare for another wave, the delta variant.

Vets in Weld County, Colorado have determined that a horse there has tested positive for West Nile virus, and local health officials in La Plata County, Colorado, near Durango, have reported that a sample of fleas has tested positive for Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes bubonic plague.

We dare not forget the other form of pestilence, insects. Sawflies can wreak havoc upon a wheat field, and swarms of Africanized honey bees called killer bees can attack human beings and livestock.

Then, because we are required to live on Planet Earth, we have little say-so in what Mother Nature decides. She outfoxes all of our pitiful attempts to predict her variable moods.

In a matter of minutes, a hail storm can destroy fields of wheat, sugar beets, corn, or beans. A heavy rain miles away can cause a flood here, where it is dry. Then, men and women continue to gape in astonishment at the devastation that tsunami’s, earthquakes, volcanoes, and forest fires can produce.

For example, on June 24, 1976, my dad’s wheat fields, located fifteen miles southeast of Sterling, Colorado, stood more than waist high and was difficult to walk through, a better crop than usual. He was most anxious to cut it in three or four weeks and put it into the bins.

That night, a five or six-inch rain fell on my dad’s farm. Hail and high winds pulverized the wheat crop. The next morning my dad and I stared at what was once a wheat field, but now looked more like summer-fallowed ground. The wheat crop was gone, shredded beyond recognition.

Then, the soil atop the hills of the summer-fallowed ground washed down into the draws, leaving a hardpan. I had to bounce on an International 806 tractor for days, pulling sweeps and a rod back and forth across that pitted hardpan, in order to work up enough soil to plant next year’s wheat crop.

The night of the storm we also lost the use of one of our two tractors for the rest of that season, because I had parked it the night before in a gravel pit, that filled with water and covered the tractor.

Those were hard days. I thought, “this has to be the worst,” but Mother Nature had a different idea.

Six weeks later, on Saturday evening, July 31, 1976, an estimated twelve inches of rain fell in just four hours in the Big Thompson Canyon, east of Estes Park.

A wall of water twenty feet high rushed down the canyon, toward Loveland, at a speed of 14 miles per hour. It picked up gigantic boulders and pitched them aside. In all, “the flood destroyed 418 homes, 52 businesses, and 400 cars,” along with campers, and dozens of propane bottles that floated away.

Of the 4,000 people in the canyon that Saturday night, 144 people drowned, and of those, five bodies were never found. One who died was Colorado State Trooper Willis H. Purdy, who stayed long enough in the canyon to turn back all travelers coming up from Loveland.

His last transmission came at 9:00 p.m. “I’m not going to make it out of here. Warn everybody below. The water is coming, and they need to get out.” His superior officers said, “That transmission, that order, that directive, is credited with saving hundreds of lives.”

If I remember correctly, I met Officer Purdy once. In the mid-1960s, he was a patrolman based in Logan County, in northeastern Colorado, and he came to a 4-H club meeting that I attended. He spoke to our club’s members, about driving safely, and he showed us pictures of numerous accidents.

Last weekend marked the 45th anniversary of the Big Thompson flood.