By William H. Benson

The Parallel Lives

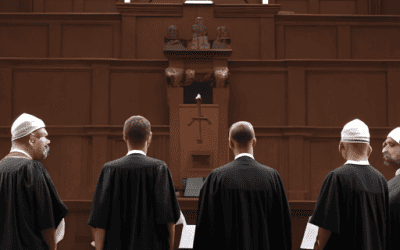

Of The NOBLE AMERICAN RELIGIOUS THINKERS AND BELIEVERS:

Roger Williams VS. Cotton Mathers

NEW ARTICLES

Daniel Defoe

Years ago, in these pages, I confessed that I have read Daniel Defoe’s 1719 fictional tale, “The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe,” multiple times, as well as listened to the audio version.

Crusoe’s ability to build a life alone on a deserted island in the Caribbean that lasted for over two decades I find fascinating. Scholars label the book “the father of the English novel.”

With a little digging and research, I learned that Daniel Defoe’s own life was as fascinating.

The man was in and out of legal trouble, often for writing libelous political comments about others. He was in and out of financial trouble, for insuring ships that failed to return to England with the goods, or for running a business into the ground, out of cash, out of profits.

Bankruptcy courts, arrest warrants, harsh judges, the pillory, and time spent in a debtors’ prison was part of Daniel Defoe’s resume. Misfortune hounded him. Of himself, he wrote, “No man has tasted differing fortunes more, and thirteen times I have been rich and poor.”

He may have died when hiding out of sight from his creditors.

His marriage to Mary Tuffley though was stable, eight children and 47 years together.

In 1692, at the age of 32, Defoe declared himself bankrupt because of a debt of 17,000 English pounds. For ten years he struggled to pull himself out of this predicament.

Yet, Defoe was a prolific writer, 545 titles across a multitude of subjects over different genre: politics, religion, drama, pamphlets, tracts, travel, history, advice, satire, poetry, domesticity, science, technology, propaganda, war, and a host of others.

Indeed, “The Oxford Handbook on Daniel DeFoe” lists 36 chapters, each written by a different modern scholar on some aspect of Defoe’s works. The first is entitled, “Defoe’s Life and Times,” and the last is “Defoe on Screen.”

From 1704 until 1713, Defoe wrote and published a periodical, “A Review of the Affairs of France,” three times a week, reporting upon events during the War of the Spanish Succession. That meant he faced a deadline every couple of days, an unimaginable amount of stress.

In 1702, Defoe published a 29-page pamphlet, “The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters; or Proposals for the Establishment of the Church” and fell into deep trouble.

In it, Defoe argued that the English monarch and Anglican church officials must exterminate the Dissenters, those Protestants who refused to conform to the Church of England.

He wrote, “If ever you will establish the best Christian Church in the world. If ever you will suppress the spirit of enthusiasm. If ever you will free the nation from this viperous brood. If you will leave your posterity free from faction and rebellion, this is the time.

“This is the time to pull up this heretical weed of sedition, that has so long disturbed the peace of our church, and poisoned the good corn.”

People read his words and felt outraged. Although no author’s name appeared in its pages, his enemies quickly identified Defoe and pressed charges against him for seditious libel.

He was arrested in May of 1703, and a judge found him guilty. Defoe was ordered to pay a stiff fine, to stand in the pillory three times, and to serve a lengthy jail sentence.

Most literary scholars are convinced that Defoe wrote this pamphlet as tongue-in-cheek, not to be taken literally, but as a hoax to show how absurd political and religious leaders can act and think. However, “the irony blew up in Defoe’s face.”

According to Daniel Defoe, September 30 was the day that Robinson Crusoe swam to shore from a sinking ship, once it stuck fast to a sand bar. The other ten men drowned. Each year on September 30, on a post, Robinson notched another mark, and thus kept a tentative calendar.

For me, the final days of September marks another birthday, another anniversary. I married for the first and only time two days after my birthday, a convenient way to remind me.

Secession and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln faced an absolute calamity on March 4, 1861, the day when Chief Justice Roger Taney administered the oath of office to Lincoln at his inauguration.

Already seven states from the South had seceded, or withdrawn, from the Union because voters had elected Lincoln President of the United States. Southern voters believed that Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery into western territories, like Kansas and Nebraska.

South Carolina voted to secede on December 20, 1860, forty-four days…

Election of 1864

Throughout the year of 1864, President Abraham Lincoln believed that he would lose the election in November. He admitted in August, “I am going to be beaten, and unless some great change takes place, badly beaten.” The odds were stacked against him.

Plenty of voters in the Union had reason to despise, even hate, Lincoln.

Tunnels and war coincide

People burrow into the subsoil, build tunnels, plus storage rooms, and stockpile food and water, for one reason, and that is to stay alive. Atop the ground, in the open air, in the sunshine, they feel oppressed, insecure, and poised to die or suffer an injury.

On July 4, 1863, thirty-one thousand Confederate soldiers, trapped inside Vicksburg, on the Mississippi River, surrendered to the Union’s commanding officer, Ulysses S. Grant, on the forty-eighth day of Grant’s siege of that town.

During the siege, civilians had dug some five hundred caves into the hillsides, and fitted them out with “rugs, beds, and chairs.” One cave dweller said, “We were in hourly dread of snakes. The vines and thickets were full of them.”

What can I achieve with Greek mythology?

What is the good that comes from knowing even a little about the ancient Greeks’ religion?

I prefer to learn of actual people who once lived in a historical setting, a time and a place. Greek mythology, instead, is a collection of make-believe fantasy stories I would like to know more of, but I find it hard to gain much traction from them, practical use. I wonder.

Mark Twain disparaged the whole notion. “Classics,” he said, “are the books that everybody wants to claim to have read, but nobody wants to read.”

After all, Greek religion is mythology, a series of stories about the gods and the goddesses whom the Greeks believed resided on or near Mount Olympus.

They included a dozen Olympians: Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Hestia, Her

Steve Inskeep’s new book: “Differ We Must”

Since 2004, radio personality Steve Inskeep has hosted National Public Radio’s “Morning Edition.” During Covid lockdown in 2020, at home with time to spare, Inskeep researched and wrote a book that was published this past week.

Inskeep found its title, “Differ We Must: How Lincoln Succeeded in a Divided America,” in a letter that Abraham Lincoln wrote to his good friend Joshua Speed, dated August 24, 1855.

Last week, Inskeep explained to Amna Nawaz of PBS News Hour, and Scott Simon of NPR, that Speed was from Kentucky, that he was from a rich family that owned more than 50 slaves. Speed approved of slavery. Lincoln also was from Kentucky, but his family was poor, and Lincoln hated slavery.

Peering into the future

Peering into the futureSome people possess a talent to peer deep into the future. In Biblical times people called them prophets. In the Middle Ages, people believed them wizards. Today they are economists who make projections based upon previous business data. Thomas...

Older Posts

The discovery near Motza, Israel

The main highway running east to west across Israel’s width is Highway One. It connects Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to the Jordan River Valley, near Jericho.

In 2012, highway contractors working 5 kilometers west of Jerusalem near the town of Motza uncovered a Neolithic town, home to perhaps 3,000 people at one time.

A new thing, an interstate highway, led to a discovery of an old thing, a town.

Tel Motza is now the largest Neolithic site in Israel. Archaeologists define a Tel as “a mound or small hill that has built up over centuries of occupation.” Excavators dig down through the layers until they find a bottom layer.

Archaeologists uncovered stone tools made of flint—arrowheads, axes, sickle blades, and knives—as well as human bones, clay figurines, grain silos, and a temple.

Books and censorship

The list of banned, censored, and challenged books is long and illustrious.

“Decameron” (1353) by Giovanni Boccaccio, and “Canterbury Tales” (1476) by Geoffrey Chaucer were banned from U. S. mail because of the Federal Anti-Obscenity Law of 1873, known as the Comstock Law.

That law “banned the sending or receiving of works containing ‘obscene, ‘filthy,’ or ‘inappropriate’ material.

William Pynchon, a prominent New England landowner and founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, wrote a startling critique of Puritanism, that he mailed to London and had it published there in 1650. He entitled it “The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption.”

A summer’s day

Popular song writers will, on occasion, dub into their lyrics references to summer.

In 1970, Mungo Jerry sang, “In the summertime, when the weather is high, you can stretch right up and touch the sky.” In 1972, Bobby Vinton sang, “Yes, it’s going to be a long, lonely summer.” In 1973, Terry Jacks sang about enjoying his “Seasons in the Sun.”

In 1977, in the film Grease, John Travolta and Olivia Newton John sang a back-and-forth duet about their “summer days drifting away, to summer nights.”

70th Anniversary of the Korean Armistice Agreement

Last Thursday, July 27, 2023, North Korea’s leader Kim Jon Un presided over a military parade that celebrated the 70th anniversary of the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement that ended the Korean conflict, from June 25, 1950, to July 27, 1953.

North Korea’s Foreign Ministry announced

Abraham Lincoln: infidel or faithful?

Abraham Lincoln: infidel or faithful?The two books that Abraham Lincoln read often and loved the most throughout his life were the King James Bible, published in 1611, and William Shakespeare’s works, first published as the First Folio in 1623, both the best of...

Four trials

Two trials in American history stand out above the others, the Salem Witch Trials and the Scopes Monkey Trial. Both were of a religious nature.

The two serve as bookends on America’s history, the first in 1693, in the years after New England’s founding, and the second in 1925, early in the twentieth century.

The trial at Salem Village, Massachusetts sought to identify and then execute those unseen spiritual forces, the witches, who, the village’s officials believed, went about in secret performing evil deeds in and around their community.

One of University of Northern Colorado’s 2020 Honored Alumni

William H. Benson

Local has provided scholarships for history students for 15 years

A Sterling resident is among five alumni selected to be recognized this year by the University of Northern Colorado. Bill Benson is one of college’s 2020 Honored Alumni.

Each year UNC honors alumni in recognition for their outstanding contributions to the college, their profession and their community. This year’s honorees were to be recognized at an awards ceremony on March 27, but due to the COVID-19 outbreak that event has been cancelled. Instead UNC will recognize the honorees in the fall during homecoming Oct. 10 and 11……

Newspaper Columns

The Duodecimal System

For centuries, the ancient Romans calculated sums with their clunky numerals: I, V, X, L, C, D, and M; or one, five, ten, 50, 100, 500, and 1,000. They knew nothing better.

The Thirteenth Amendment

On Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and by it, he declared that “all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are and henceforward shall be free.” Lincoln’s Proclamation freed some 3.1 million slaves within the Confederacy.

The Fourteenth Amendment

After Congress and enough states ratified the thirteenth amendment that terminated slavery, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This law declared that “all people born in the United States are entitled to be citizens, without regard to race, color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” The Act equated birth to citizenship.

The New-York Packet and the Constitution

Jill Lepore, the Harvard historian, published her newest book a month ago, These Truths: A History of the United States. In a short introduction, she describes in detail the Oct. 30, 1787 edition of a semi-weekly newspaper, The New-York Packet.

Mr. Benson’s writings on the U.S. Constitution are a great addition to the South Platte Sentinel. Its inspiring to see the history of the highest laws of this country passed on to others.

– Richard Hogan

Mr. Benson, I cannot thank you enough for this scholarship. As a first-generation college student, the prospect of finding a way to afford college is a very daunting one. Thanks to your generous donation, my dream of attending UNC and continuing my success here is far more achievable

– Cedric Sage Nixon

Donec bibendum tortor non vestibulum dapibus. Cras id tempor risus. Curabitur eu dui pellentesque, pharetra purus viverra.

– Extra Times

FUTURE BOOKS

- Thomas Paine vs. George Whitefield

- Ralph Waldo Emerson vs. Joseph Smith

- William James vs. Mary Baker Eddy

- Mark Twain vs. Billy Graham

- Henry Louis Mencken vs. Jim Bakker